Editorial Note: The following is reprinted with permission from Mary Nikkel’s Substack. It was originally published on June 12, 2025.

By Mary Nikkel

I was trudging through a slurry of chemicals, holding a metal rod with a razor blade attached to the end, when my 11-year-old legs gave out. I slipped, landing on hands and knees in the slurry of wax stripper and peeling floor sealant that oozed half an inch deep on thousands of square feet of tile.

I’d been meticulously scraping off bits of floor wax that the chemicals and buffing machines hadn’t stripped perfectly when I fell. It’s not that I slipped; it’s that we were around hour 9 of working, and my child’s body simply gave out. I cowered frozen in the acrid chemicals, my chest heaving, feeling the floor stripper seeping through my pants and scalding my sensitive skin.

I was still trying to will myself to get up when my boss, who was also my father, walked around the corner.

“Get up,” he said in a fully neutral tone. “We’re not finished yet.”

I used my rod with the razor like a staff to pull myself to my feet, trembling all over. Dripping with toxins, I kept moving, peeling away the floor’s finish so it could be relaid later.

That night ruined my favorite pair of pants, a white and sage green pair of crepe capris that I’d salvaged from one of the many massive bags of hand-me-down clothes my family often received from compassionate acquaintances. It was two days before Christmas, and we had several relentless days of work like this ahead. Still, when I curled up after midnight under the blankets of my bed in a room I shared with all 3 sisters, I took time for my nightly ritual of pulling out a flashlight and journaling.

“My hands are covered with scrapes and blisters,” I began. “A huge bruise is forming on my knee. My back is aching. Why? We stripped the wax off the floors in the new building. 10 ½ hours of back-breaking, exhausting work. I’m only eleven.”

I’m only eleven.

I went to work for the first time when I was about 8 years old.

Since returning from missionary work in Zambia 5 years prior, my rapidly growing family had lived below the poverty line. I didn’t know words like “food insecurity” back then, but I knew that sometimes dinner was just a pot of plain beans we’d split, and the only allowed snack was usually 2-3 saltine crackers eaten at precisely 10:00 and 3:30.

The modestly-sized evangelical church we attended at the time reached an agreement with my father: he would take on a custodial contract for the two buildings. His staff would be his three oldest kids, then 13, 10, and 8 — children expected to deliver the ethic and work quality of adults.

I felt very grown-up when I was told I was going to work. I was not paid at all in the beginning. Later, I would be paid $10 per month. I was told that if I didn’t go to work, or if I did the job poorly, my baby siblings (3 of them at the time) would be starving on the streets.

I would have jumped into traffic for any of the smaller kids without a second thought. So I went to work.

We started work on Thursdays and Fridays after dinner, because my dad worked his primary job during the day. We worked at least those two days a week, plus extra projects as needed that could take up as much as a week or more.

The church’s fellowship hall had one full wall that was all windows. I still remember how every single night of work began: my father walking up to that bank of glass and lowering the sectional shades, one sharply descending shadow at a time.

“It will keep the sun out,” he said.

“And anyway,” he added one time, as a casual after-thought. “We don’t want anyone driving by, looking in, and getting the wrong idea about why kids are here.”

I’d spent my whole childhood being taught how to hide from CPS, so this made sense to me.

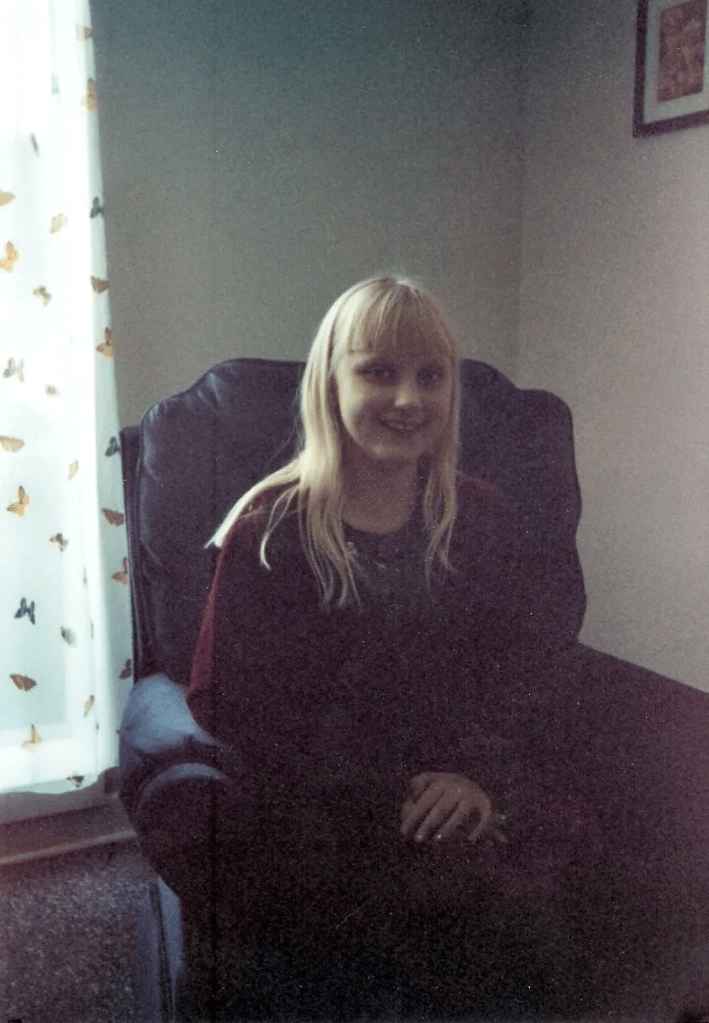

Usually, we’d be driving home from work around midnight. My family’s big 15-passenger vans rarely had working AC, so during the summer months I’d crack the window at my spot beside the sliding door. I’d lean on the cool metal, meet the reflection of my white-blonde hair and starkly blue eyes against the sluggish southern air.

In my near-militantly consistent journaling habits during those days, almost every illustration I drew of myself featured bags like black crescents drawn under my eyes. Like I couldn’t imagine myself without the exhaustion.

My parents were solving the problem of our poverty in the only way that came to mind for them within the strictures of our intense spiritual system. Wives didn’t work in our world, so the kids went to work instead. We were paid in the currency of shelter, being kept safe enough.

But now my child’s body and heart had a problem too: how do I understand the ruthless toll on my wellbeing? I solved that problem the only way my small subconscious self could: maybe my body was meant to be a machine. Maybe no amount of tiredness or vulnerability or smallness earned worthiness to be protected. Maybe if I stopped producing, being productive, working, something terrible would happen to the people I loved.

As I got older, we added more cleaning contracts, and my coworker siblings and I got paid slightly more for them. An architectural firm, a car dealership, a daycare: we kept adding new locations to clean on both regular rotation and for special projects.

But none of them impacted me quite the way the first job did. We cleaned that church for 10 years, long after we’d stopped attending it and moved to a cult-like chapel a few miles away. Part of why we stopped attending was due to utterly vicious bullying aimed at my siblings and me.

My first memory of a panic attack is from around the same time we started working the cleaning contract. I was told to go in to children’s church. My whole body seized in sudden terror at the thought of being surrounded by kids who called me stupid, made fun of my clothes, mocked our homeschooled status. I ran and stood in a corner, hyperventilating, until an adult came and dragged me into the room.

I was acutely aware that when I worked, I wasn’t just making a statement about what my body was good for. I wasn’t just engaging in one of the most looked-down-on jobs in society. I was also cleaning up the dirt and trash of people who genuinely believed I was garbage.

It instilled in me an immense sense of inferiority. I didn’t believe I’d ever work anything other than manual labor. I didn’t believe I deserved to.

When I got a little older and had a pretty intense spiritual encounter, I started to wonder how I could transform the experience of my weekly cleaning work. I was immensely inspired by the story of the Hebrew hero Joseph, who continually turned tragedy into abundance.

So as I cleaned toilets, I would pray for my bullies. I would wish them well while literally scrubbing up their shit.

It was a lot of pressure to put on myself as a teenager, and I would not necessarily prescribe the approach to others. But for me, I did find it transformed the menial into something sacred — and it helped me survive the ignominy of the tasks at hand, connecting me to the compassion that felt truer than the grime on my skin.

Another thing that helped me survive is that this was one of the only places we had access to contemporary music (which was strictly forbidden at home). We would sneak into the youth group room, where they often had DVDs of Christian rock music videos. My siblings and I would huddle around the TV, entranced by videos of bands like Switchfoot, Disciple, Skillet, Relient K, and RED. I found immense comfort in that alternate world I was getting a glimpse of.

When the church severed our contract to cut costs, I was made to feel that the world would end. It didn’t; it carried on. We still had other contracts that I worked through college.

But years later, I am continually haunted by the feeling that if I’m not working, calamity is imminent for everyone I love. Every time I have had to take medical leave is an exercise in excruciating mental anguish. Every job I’ve had to move on from has been grieved like a death. How do you stop seeing yourself as a productivity machine when being one used to feel like life and death?

It has impacted every area of what I accept for myself. I have struggled to know what is reasonable treatment in a workplace, grasping at scraps of care from toxic employers and thinking they were truly being accommodating. One of my first jobs, I endured sexual harassment for a whole summer from a much older man and gaslit myself into thinking I was making it up. I believed I was just lucky to be working.

My siblings and I have a whole genre of dreams that are just about being in those old church buildings, places we haven’t entered in 15 years. We joke about it. We’re haunted by it.

In my four years working with a nonprofit, I’ve had to grapple with the ghosts that rise when I read about kids working. I read and write stories infinitely worse than my own on a daily basis, stories of trafficking and exploitation. I have a pretty strong sense of separation between my work and my wounds.

And still, sometimes there’s a little girl in me trapped on her hands and knees in acid, just wanting to be told: it’s OK to be tired. It’s OK to rest. It’s OK to take a break before your heart is literally giving out.

In this way, as in many ways, my long-term illnesses have given me gifts in strange forms. I write this from a hospital, where I am allowed infinitely more rest and bodily safety than I had as a child (and healthcare at all, which I also did not have until my late 20s). Having no physical ability to keep demanding from my body what it delivered my whole life has forced me to learn boundaries and compromises. I don’t think I ever would have started that deeply challenging actualization if I’d had a choice to keep running myself ragged. Facing death took choice away: it was slow down or die.

I have usually worked a minimum of two jobs, and right now is no exception; I have two wholly separate careers I am passionate about. It is still a constant work in progress, learning how they can coexist with my chronically sick body. The progress is slow, but it does exist. My work weeks look more like 50 hours instead of 60+ these days. I have friends and professionals to call me out when I’m falling back into overwork as a form of self-harm.

And when the scared little girl says “stop, this is hurting me” by cowering into the acidic collapse of starving or self-harm or suicidality, I’m trying to learn to listen.

Right now, protections for kids in the workplace are being challenged in the legislature across the United States. What I experienced would still be illegal, in any one of the 50 states. It might not stay that way. Freedom United is great resource for staying up to date on protections for kids and participating in vital petitions and calls to lawmakers.

Mary Nikkel is a music and nonprofit writer and photographer. She writes about all things mental health, meaning, and music. Mary is the founder of Rock On Purpose, a music news website that talks about rock music that heals. She writes about recovery, mental health, life, death and hope on her Substack. You can learn more about her work and writing at marynikkel.me.