Content note: child sexual assault

By Stephanie Gail Eagleson

What’s a “daddy cult”?

When progressives hear the word “patriarchy,” they might think of systemic misogyny in politics and business. When I hear that word, I think of the religious framework that kept me and my six younger siblings trapped in our own home. A “daddy cult” is a nuclear-family-sized cult designed and enforced by the father. In my case, the father was a racist, misogynistic, fundamentalist child abuser.

My father raised me on 16 acres of land in the rural American midwest: we lived along half a mile of dead-end gravel road a good 30 minutes from the nearest Walmart. He taught his children that our highest calling in life would be to establish his vision of a familial commune, one free from all the corrupting influences of the outside world.

Corrupting influences that might challenge his absolute despotic authority.

My job was to either marry myself off to support some other man’s fiefdom (which was hard to even begin to do because of the extreme social isolation my father deliberately inflicted on us — I’m serious, COVID quarantine is nothing compared to that.)

Or stay home indefinitely, engrossing myself in menial labor and sycophantic quietude as my father’s “slave girl.”

Yes, he called me that. It was a joke.

He meant it.

I spent many years growing up wishing I had been born a boy and imagining myself as a man in any number of daydreams, because in my world, only men had respect, agency, opportunity — voice. As a female in this context, my voice was not my own. Everything I did had to be marketed to my father in such a way that it furthered his agenda, his reputation, or his ego. He treated me as his property, either to be used or ignored at his behest.

This abuse first took the form of molestation when I was a baby.

I was about 18 months old. I remember multiple incidents very clearly, which is not surprising if you consider the fact that I was quite verbal for my age — I had conversations with my father about this early sexual abuse at the time it was happening — and that I retain multiple other memories from that time period as well.

I have spoken to other family members who, it turns out, were aware of the molestation at the time but did not understand what it was. They validated my account thoroughly, which is a rare grace afforded victims of sexual assault, I’m well aware. One person expressed remorse that they did not know enough at the time to do more than threaten to expose my father to his church’s leadership.

Shockingly, this threat apparently prevented my father from molesting me further for well over a decade.

Other sexual infractions that he committed against me later on were comparatively slight.

The majority of my abuse at the hands of my father was psychological: he leveraged mental, emotional, and spiritual torment against me for decades in order to control my thoughts, behavior, and resources to serve his purposes. He also occasionally employed financial abuse, laying claim to my money as his own and spending it as he saw fit, and physical abuse.

For years I had lost the memory until my brother reminded me that the last “spanking” I received from my father was in the kitchen. I was in my late teens or early twenties, and my father had gathered the other seven members of the family around to witness justice wrought upon my disobedience.

I cannot at all remember what the point of disobedience was, only that it involved an ethical principle I refused to bend to accommodate his wishes. I remember gripping the sides of the marble countertop and successfully bottling every tear and cry for the first time in my life because I was determined my siblings would see how it was possible to stand up to him — even as it never occurred to me to leave the house or call police.

My father was my jailer, my abuser, and in many ways, at least for a time, my god.

My father was also the first one to tell me the story of the Gospel in a way I could understand, appreciate, and accept, again from a young age.

While only a minority of Christians grow up in a rural isolationist daddy cult (though I have personally encountered far more of us than you would ever hope to hear about), I have seen disturbingly similar threads of abuse play out across Evangelical Christianity.

I am not unlike many, many others within Christianity who have found Jesus through despicable men.

In particular, I have spent the past weeks processing the meteoric fall of the late Ravi

Zacharias — lauded conservative evangelist and, after the conclusion of an investigation four years too late, verifiably pathological liar, sex abuser, and rapist.

Like most pillars of the colloseum of abuse culture in Evangelicalism, Zacharias was never called to account before his reputation reached artifact status. His institution and influence stand today, battered but irrevocable.

And he is not alone. Compromised celebrities like Bill Hybels, Carl Lentz, C. J. Mahaney, Andy Savage, and the individual formerly known as the United States President are allowed to thrive in Evangelicalism. Many are still celebrated.

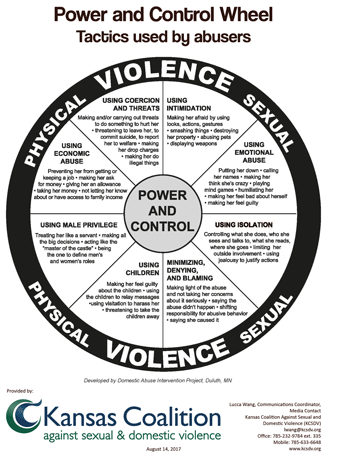

Dangerous beliefs about forgiveness, restoration, and justice — theologically untenable, demonstrably harmful, and yet wildly popular — have created toxic relational patterns of power and control across Evangelicalism, and it is in fact such systems of power and control that define the central dynamics of abuse, as illustrated by the widely respected Duluth Model:

An abject failure to understand abusive power dynamics has led most Evangelicals to excuse and minimize abuse in their midst for decades.

Survivors of religious abuse across the nation, myself included, have watched this drama play out over and over. We have heard the message loud and clear: speak up if you want to be shut down, thrown out, and vilified. Lori Ann Thompson—the first woman to raise allegations against Zacharias—is far from an isolated example.

Advocates for reform within Evangelicalism are routinely mocked, denigrated, and shunned,

particularly by wealthy and influential leadership.

We are labeled as divisive, bitter, and contentious — a threat to the reputation of God himself.

How the creator of the universe would have any use for a mortal PR team is beyond me, which leads me to conclude that Evangelicals, by and large, equivocate their own reputation on God’s behalf with the renown of the omnipotent trinity itself. But an idol is no substitute for Deity, and the temple we’ve constructed to a false god is crumbling around us.

Yet those responsible for creating this danger seldom fall prey to it. Instead, the religious arena victimizes and re-victimizes countless innocents, up to and including their actual deaths, as we have witnessed this past week in Atlanta, where a Southern Baptist man slaughtered nearly a dozen women, many of them Asian, to “eliminate temptation.”

A white male evangelical set his own perception of his own standing before God and others before the literal lives of fellow humans. This is not a new phenomenon: I have seen countless others within Evangelicalism behave the same way. Sometimes lives are completely snuffed out, but more often life is slowly strangled from victims over decades.

So how do we heal?

Despite all my abuse, in a Providential twist, I was able to earn a four-year degree at a private liberal arts college.

Neither of my sisters were given that opportunity as they grew up, and I have good reason to believe my dad resented my higher education after I had attained it (I had apparently become a feminist in the process and thus an enemy of his state).

I eventually escaped my father’s intended commune and married — into an upper middle class religious homeschooling family. Because my husband wasn’t a patriarchalist, however, I could trade the daddy-cult in for a culture of bog-standard sheltered + privileged conservatism. I’ve spent my married life detoxing from my abused childhood, having a few kids, and then turning around and detoxing from abusive theology.

In each horribly toxic context of each chapter of my life, one thing remained true. God was with me.

God provided a means first to survive it, then to escape, often by bizarrely up-cycling the very experiences of abuse I endured until, finally, I could work from a place of stability and security to deconstruct them entirely.

This has been painful, long, traumatic. And yet I recognize that as a straight white woman I had access to resources that so many others do not.

After some years of deconstruction, therapy, educational resources like the Power and Control Wheel, the support of fellow survivors and advocates, and the plain sobering fact that the abuse I suffered was mild compared to the stories of most others I’ve heard, I can say that I am well on the path to healing.

But I am still in-process, and the journey is not straightforward.

The greatest deterrent to the transition from surviving to thriving, for me, has been that favorite subject of Brene Brown’s research: shame.

Unhealthy shame is discomfort that has been weaponized by others to exert power and control over us. It is a tool of abuse. Because of this, I was raised to think discomfort itself is shameful, when in fact discomfort is one of the most necessary, powerful, trustworthy tools human beings have built into them. Discomfort is arguably the antidote to shame.

What I learned from Braving the Wilderness (thank you, Brene) is that while shame pressures us to retreat into our “ideological bunkers” and conform to the demands of our tribe—in my case, a tribe ruled by abuse culture — discomfort is the emotional experience that characterizes striking out on our own to uncover and adhere to real truth when we tire of settling for the party line.

Developing a spine that won’t settle for easy answers or pleasing people is painful. When we consciously choose discomfort derived from our own uncertainty and others’ rejection of us, we have shaken off our conscription to shame.

As I have built my faith back from the ground up, here are the foundational questions the wreckage has forced me to tackle and resolve:

What do I do when I am assaulted by the truth that the man who led me to Christ may well have never known and accepted Jesus to begin with?

Or, worse, if he ever did, that he never allowed the power and goodness and truth and love of Christ to prevent him from committing unspeakable sins against the most vulnerable in his care?

What do I do when a spiritual parent uses what gave me life to bring death to others, or to myself?

Here is what I have done: I have clung to the life that was given to me, because it is life-giving.

It didn’t come from the man who called himself my father—that mere, distorted, destruction-bound human soul.

It came from the source of life itself. A source that will not betray me. One that will not wield good for evil. One that will tear down and burn and blacken into nothing all that has ever hurt me, all that has ever wounded me, all that has ever torn my heart out and eaten it in front of me.

God of peace, of justice, of righteousness, of truth, of love gives me life and hope and healing. Not my dirt-born parent: my infinite-always-was parent. Jesus got through the morass of evil embodied by my earthly father when no one else could. The Holy Spirit reached me, and she did not leave me alone. She sat with me in all the agony and misery and torture and wickedness until it passed.

All three are with me still.